Your family history is inherently all about you. Where you came from, how your ancestors lived, how they died, and sometimes why they lived as they did shape who you are today. The first step to understanding these people is to figure out what you already know.

However complicated writing out your family tree seems, you probably already know a lot. But then, how do you find someone you don’t really know? How do you prove anything? Won’t it take a long time? Will it ever end? What if I don’t have access to records?

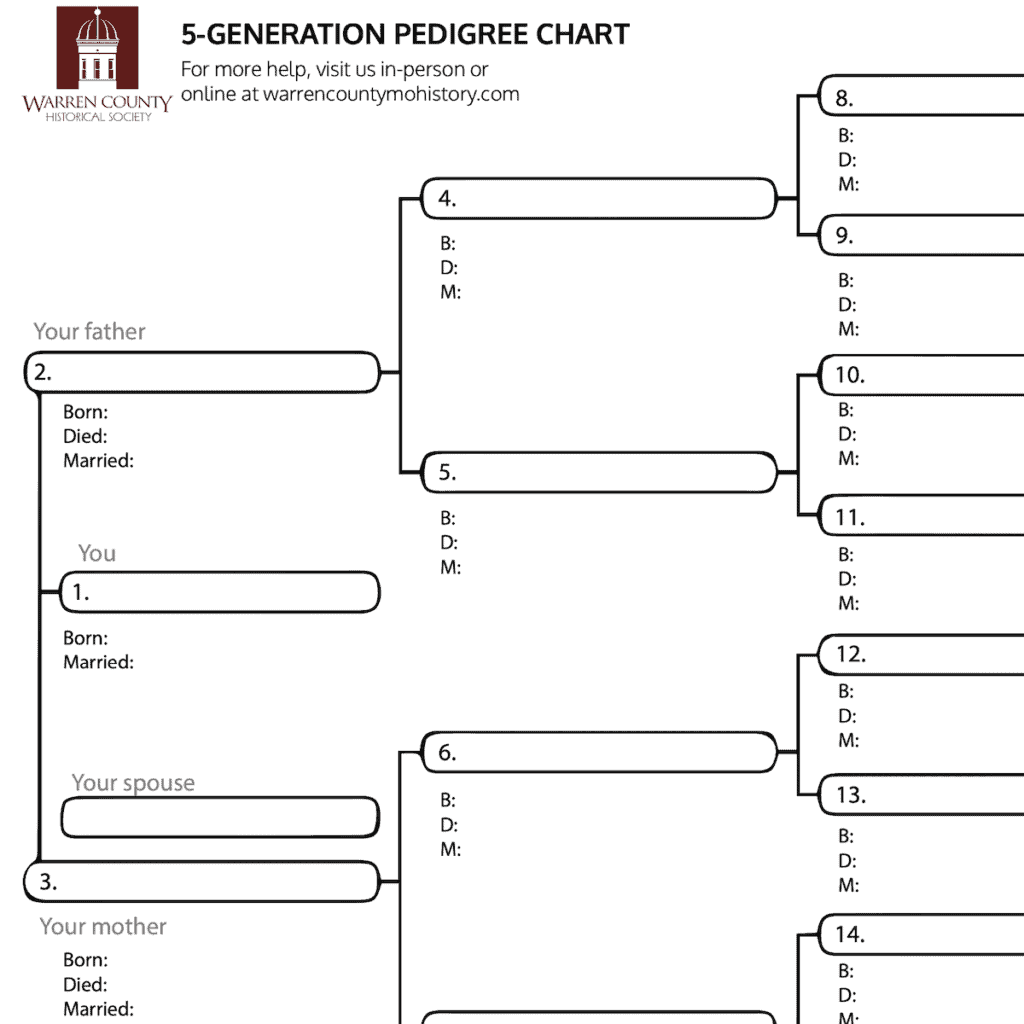

Step 1: Download a family history pedigree chart

Like painting your kitchen, you’d probably prep the space by laying down tarps and taping the edges to give you boundaries and define the space. A pedigree chart works the same way.

- Download this free 5-generation family pedigree chart

- Fill out your name and your parents’ names in slots 1, 2, and 3.

- Write what you know about the marriage, birth, and death dates of yourself and your parents.

- If you know more, write your grandparents’ names in slots 4, 5, 6, and 7. Continue as far as you can. Most people only know the grandparents or maybe the name of their great-grandparents.

Digital services like Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org will handle many of the trees and pedigrees for you. We recommend using these digital services as your family tree grows. But this 5-generation pedigree chart is useful on paper for the next step.

Free 5-Generation Pedigree Chart Download

Looking to get started with your genealogy research? Follow our handy guide and see how you can use this to jumpstart your family tree.

Step 2: Talk to family members

Depending on your age and the age of your family members, the best place to source your family history is from living relatives. Talk to your parents, grandparents, and other family members about who they remember in their lives.

If they’re not alive or available, some extended family may be able to help, like aunts or great uncles.

Ask them questions like:

- “Do you remember your grandparents or great-grandparents?”

- “Do you remember when they were born, married, or died?”

- “What were they like?”

- “Did they serve in the military? Do you know about any military records?”

- “Do you know if any death certificates, marriage certificates, or birth records are in storage anywhere?”

If your grandparents are still living and if they remember their great-grandparents, that fills out four generations of your 5-generation research. For a middle-aged person today, that could take you as far back as the U.S. Civil War!

- Talking with older relatives can help yield discoveries about other distant relatives like cousins or aunts.

- They may all have family stories to tell about where someone lived or how they died.

- They may remember their personalities and reveal characteristics — like a hot temper or a cool calmness — that was passed along to you.

These valuable clues can help you identify where people moved, lived, traveled, worked, served, and married. Plus, most older relatives will relish talking about other relatives, missing relatives, and family relationships.

Write notes down in a notebook and on your 5-generation pedigree chart. Then, when and if you decide to research more or use a software program like Ancestry, Family Tree Maker, or FamilySearch, you can quickly input notes to get started quickly.

Even if someone only remembers their parents or grandparents were born “around June” or married “sometime in the fall,” these are powerful clues to help you in the next step.

And if you don’t have anyone to talk to, don’t worry — write what you know or suspect. Try and remember if any family members made mention of people in passing from time to time. If you remember grandma saying something like, “Mamaw Ruby always used to say…” that’s a good clue her grandmother was likely named “Ruby”.

Step 3: Visit family history centers, research libraries, and online sources to verify

Historical records are increasingly digitized, making searching for records incredibly easy. What used to require trips across the country to visit courthouses, family history centers, or a local library are now available with free access or paid vital records.

The Warren County Research Library, like many state and local libraries, holds a variety of genealogical materials. Our Research Library also holds items related to the history of Warren County’s businesses, homes, prominent families, and more.

As you begin your search, here’s what you’re looking for:

- Birth records of anyone in your tree. Birth records administration varies by state, but in Missouri, many are available through the Secretary of State’s office, with free access online. These certificates prove not only the date of birth but will also list a mother and father, giving you a clue from the prior generation.

- Death records, which are also available online in Missouri, as one of several free resources. These state archives usually record the deceased’s spouse and may list parents or other next of kin. Additionally, many state death records show the cause of death — which can be incredibly interesting in detecting health patterns in your family history. Likewise, probate records shows the wills of the deceased.

- Tax and probate records include all the family records on file with the Clerk’s office or land registry. These land records show land ownership and who bought and sold what property and where, often after death when the farm or homestead transferred ownership to a spouse or next of kin.

- Military records, including draft cards and pensions, that identify next-of-kin. This is often a spouse, but in WWI and WWII, draft cards for young recruits often listed their mothers and their address and described the physical characteristics of the person enlisting.

- Church records, which are most common in early generations prior to 1930, include family histories written in family bibles. The covers of Bibles, often the only source of paper in rustic homes, included the birth and death dates of people in the home.

- Census records, which are also freely available online through many sources like the National Archives, is the most extensive collection of movement patterns in the United States. Family genealogy often starts with census records because they’re consistent, show movement every ten years, and identify everyone in the household. Professional genealogists start with census records when they don’t know where else to start.

- City directories, a feature most available in Ancestry.com, pulls listings from yearbooks and telephone books. These records often show addresses where people lived. These are most common between 1920 and today.

- Cemetery records, which include sites like FindAGrave.com, show gravestone markers of the deceased, including their birth and death dates. They are frequently buried next to spouses or relatives, leading to more discoveries about ancestors.

- Newspaper clippings, which aren’t always accurate owing to the speedy nature of local newspapers for most of history, provide clues to family information, like where a person died, who served in the armed forces, and even photos. Many newspapers are available to search online, such as through Newspapers.com (an Ancestry company). Newspaper clippings, however, are not considered a primary source for most genealogists.

As you start to build your family tree, record the links or print off the family documents you find. Use these records as proof. You can print state census records with just the page that shows your ancestors. Make notes as you go on the physical documents.

Or, use an online service like Ancestry (which is pricey but includes a seven-day free trial) or the free-to-access and use FamilySearch.org, which is built off the efforts of the Church of Latter Day Saints to digitize millions of records.

Be patient and enjoy the search, step by step

As family trees grow, you’re building connections to family lines that future generations can pick up and work with — just make sure they have access to the files. Your Ancestry account does them no good if the subscription expires or no one knows the password. That’s why family research is often done with paper. Except in the case of fire or flood, paper is future-proof against changes in technology, logins, and file formats.

Work person-by-person, too. Like solving any puzzle, start with what you know and work with what you have. And like a puzzle, much of the inherent value and entertainment is in the search itself and that feeling of plugging in just the right piece after a lengthy search.

If your ancestors settled or lived in Warren County, visit our Research Library for more. Like most historical societies across the U.S., we have amassed family history and genealogical data such as land records and local histories. These documents, books, and indexes come with talented volunteer researchers who can help answer questions.

In many communities, county courthouses, local libraries, and the Clerk’s Office can yield clues, too. Check with them before visiting to ask since every county and jurisdiction is different. In Warren County, most of the historical land and probate records are held with us at the Historical Society.

We’ve compiled a list of more helpful resources applicable to Missouri family and genealogical history:

- Names and lists of items available in our Research Library on microfilm

- Dozens of free databases online for Missouri families, including naturalization records, soldiers’ records, and more

- A list of family history files, which often include narrative stories compiled from past researchers

- A sortable, searchable list of probate records

Your family history research may become your life’s work or just a side project that occupies your free time. Genealogical research can sprawl for hours across multiple branches. Once you trace your father’s lineage back to several generations, you’ll get to do it again with your mother’s branch.

Each family member has a story to tell, too. You’ll discover things you didn’t know, like their military service — such as if they served for the Union or Confederacy or alongside General Washington in the Revolution. You’ll likely discover crimes they committed (or claim they didn’t), naturalization records, old photos, and other interesting details.

Your personal family history library starts here. What will you find?