Warren and surrounding counties suffer harsh economic hardship, prejudice during Prohibition

The Great Depression came ten years early in the Missouri “Rhineland”. The 1919 Volstead Act and the 18th Amendment banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol in the US. Until January 1920, Missouri was the nation’s second-largest wine producer, driven by wineries along the gentle bends and fertile hills of the Missouri River and around Gasconade, Franklin, St. Charles, and Warren Counties. Now, they were forced to shut down.

A few wineries clung to life nationwide, operating under temporary permits permitting narrow production of sacramental wine for communion services. Saint Stanislaus Seminary in Florissant was the only winery allowed to operate in the region.

Stone Hill Winery in Hermann lost most of its cellars and most converted to mushroom farms. One of its huge wine barrels was shipped to St. Louis, where a local monastery used it for communion wine. Mount Pleasant Winery in Augusta was the second-largest winery in the country pre-Prohibition. It featured world-renowned vineyards, cellars, and wine casks, all of which were uprooted or removed in 1920.

Then came the raids.

Nearby Hermann, Missouri saw federal agents arrive to destroy the vineyards, wineries, and breweries that had powered the town’s economy. Dark red wine ran through the streets as agents axed barrels and poured thousands of gallons and thousands of dollars of wine into sewers.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, residents of the Missouri Rhineland were strongly against prohibition and “dry laws”, which had been sweeping state legislatures and voters before national Prohibition, but not in Missouri. Voters in Warren County resoundingly voted “no” on a 1918 state-level dry law, 1,477 to 349:

| Precinct | “Yes” votes | “No” Votes |

| Warrenton | 92 | 196 |

| Truesdale | 9 | 72 |

| Pendleton | 21 | 66 |

| Wright City | 68 | 157 |

| Painter’s Store | 12 | 52 |

| Pitts | 13 | 23 |

| New Truxton | 23 | 55 |

| Week’s School House | 14 | 37 |

| Harper’s School House | 17 | 24 |

| Marthasville | 37 | 171 |

| Dutzow | 2 | 94 |

| Peers | 1 | 59 |

| East Treloar | 6 | 27 |

| Holstein | 7 | 34 |

| Hopewell | 3 | 96 |

| West Treloar | 3 | 44 |

| Rekate’s Store | 8 | 59 |

| Johnson’s School House | 2 | 15 |

| Lichte’s School House | 0 | 37 |

| Gore | 4 | 20 |

| Case | 3 | 80 |

| Upper Bridgeport | 4 | 59 |

Voters elsewhere also voted no, like in St. Charles County where they opposed state-level Prohibition measures by a vote of 3,005 to 592. The subsequent loss of $2 million a year to the state budget left a mark from a lack of inspection fees and taxes.

Commerce, legal or not, finds a way amid lax enforcement

Market forces all but demanded an illicit liquor trade in nearly every county in the country. South of Jonesburg, in a wooded hollow, the scent of mash and whispers of midnight traffic earned the nickname “Happy Hollow”. Neighbors knew, but tight-knit communities stuck together.

Local law enforcement struggled to balance the law with the voters who lost livelihoods and inheritance. Lawmen caught between federal expectations and local resistance took a lax, often racial approach.

One federal report in 1920 criticized Sheriff John Grothe in St. Charles County as “half-hearted and discriminatory”, since black men and immigrants made easier targets to arrest than white men committing the same crimes. To most area residents, federal laws were rigid, but the people were not lawless; just bound by a different kind of loyalty to neighbors, family tradition, and livelihood.

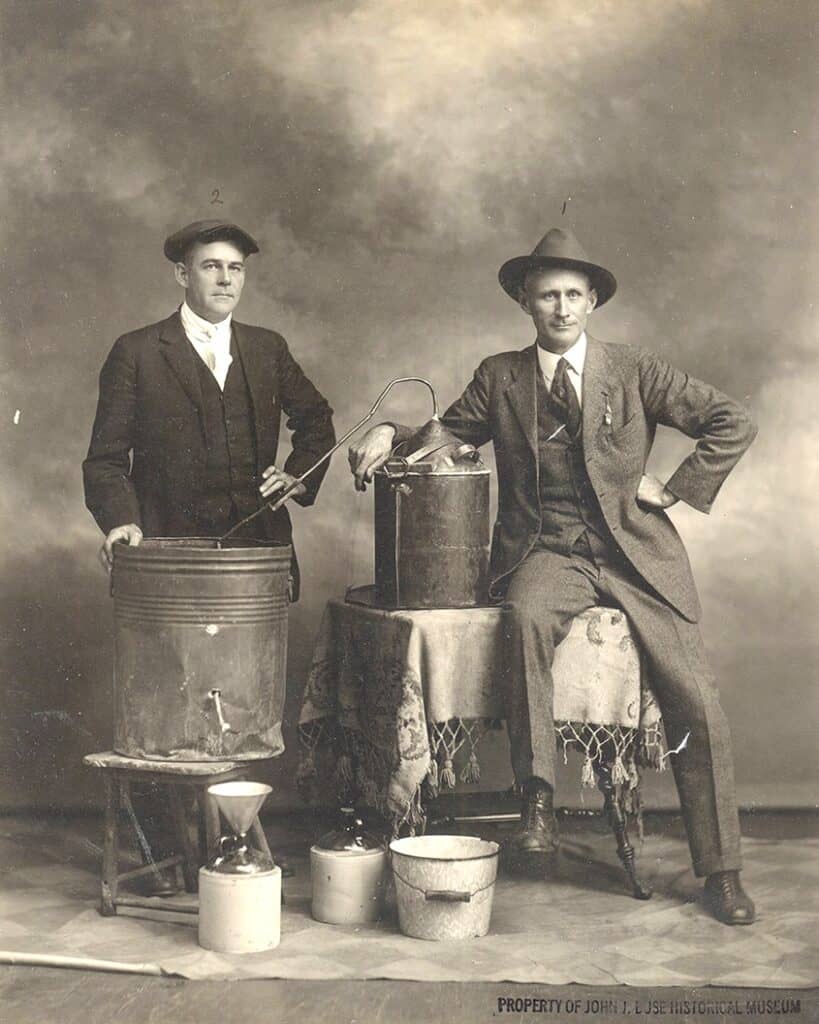

Across Warren County, men fired up stills in barns, basements, and bramble-thick woods. Trains once loaded with barrels of wine now carried jugs of moonshine, tucked in crates or passed hand to hand. Smugglers sailed up and down the Missouri River with illegal jugs of hooch bound for towns, trains, and larger river boats and ferries. The law, when it came, came late—or not at all.

Still, some token enforcement was necessary, even against white smugglers. Sheriffs, either under threat, bribe, or both, were known to raid a farmhouse with multiple stills only to smash half the stills.

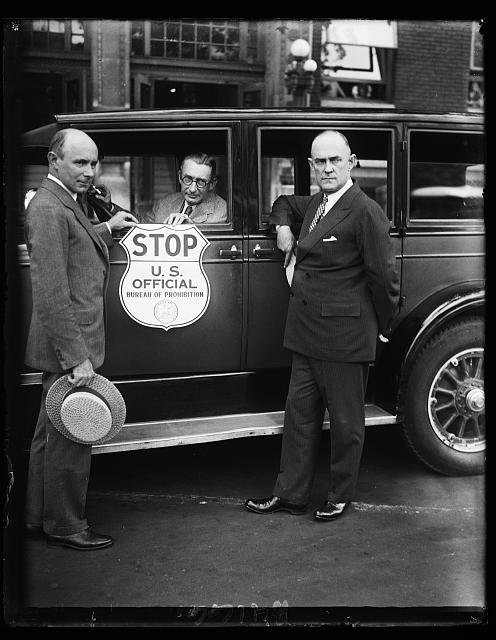

Federal “Dry Agents” conducted operations around the country with more vigor. These agents were often shown in newspapers smashing stills, pouring alcohol into the streets, and posing with arrested men.

New highways complicated the transportation of illegal alcohol, rum runners, and smugglers. Farmers distilled corn whiskey in the backs of barns, underground, or deep in the woods and drivers could ferry “white lightning” down backroads and onto U.S. 40 back and forth between Kansas City and St. Louis. What was good for legal commerce was good for illegal commerce, too. Law enforcement noted modern roads, “quickly became a conduit of alcohol and other illegal commerce.” Warren County was literally caught in the middle.

Indeed, Warren County residents were equally interested in a “nip” here and there. As one southern Warren County resident today recalled of an acquaintance:

“…[his] neighbor was known to have occasionally picked up some alcohol in St. Louis and would keep any empty bottles he consumed hidden in the grain bins at his farm. He would occasionally go into St. Louis and pick up his supply of beer and alcohol and bring it out to his farm where he would water it down.

When there was a dance in the area, from the parking lot he would survey the number of people going into the dance hall, and then would water it down even more, depending on the size of the crowd. He then snuck the alcohol into the dance where he offered it to those he believed he could trust and they would help him distribute it.”

If you knew the right hand to shake, you might get a bottle. If you knew who to trust, you might help pass it along.

Elsewhere in Warrenton, Washington, and St. Charles, former tavern owners desperate to scratch out a living converted to “soft drink” parlors or back-room clubs. Patrons were asked to “speak easy” to avoid detection or tipping off federal agents.

Juries were just as conflicted as lawmen. Juries were known to come down on convicted criminals with jail time and fines. A Warren County Grand Jury in 1924 sentenced several local men for moonshine:

Gus Kraemer, of near Pendleton, indicted for selling moonshine; unable to pay fine; sentenced to six months in county jail;

Henry Sellenschuetter, of Upper Charrette, was sentenced to two years in the penitentiary for manufacturing moonshine.

Chas. Bockhorst, of Holstein, was fined on three indictments: $100 for operating a gambling device; $200 for possession and concealment of liquor; $500 for selling liquor, making a total of $800.

H. H. Hasenjaeger, of Treloar was fined on four indictments as follows: $200 each on two indictments for possessing and concealing liquor; and $500 each on two indictments for selling liquor, making a total of $1,400.

$500 in 1924 is about $9,300 in 2025 dollars. $1,400 in 1924 is about $26,000 today.

But for every jury that found in favor of prosecutors, another virtually nullified the laws. As Prohibition wore on, juries became more sympathetic and defense attorneys grew more clever. In one St. Charles County case in 1930, prosecutors charged George Koelling with a liquor violation. The jury deliberated a mere 40 minutes before acquitting him. The prosecution almost didn’t feel worth the time and effort, which further reduced overzealous policing by local officials, despite occasional instances of unusually rowdy behavior.

In August 1924, Warren County Sheriff John Shaw reportedly left town for a day only to come back to a story reminiscent of The Andy Griffith Show when a federal prisoner escaped, went down the street to buy rubbing alcohol, went back to jail, and shared two bottles with the inmates. A Warrenton Banner report notes:

“Rubbing alcohol is sold to so many people for external application, that nothing was thought of this purchase, and no one had any thought of any person drinking it. Soon after the bottles were drained the men raved like wild men, and broke some of the windows in the jail and tore things up generally. It required several men to get the affected prisoners into a cell where they were locked up.

A number of the prisoners have the freedom of the courthouse lawn during the warm weather, and occasionally some of them are permitted to go to the store to make purchases. One of the men was so affected by the alcohol that it required the services of a physician. The wonder is that all were not killed.”

The Klan vs. local Germans

As if hardship were not enough, the Ku Klux Klan added another scourge. Emboldened by Prohibition, they saw in it a means of punishing immigrants and Catholics, especially the Germans of the Missouri River Valley. They branded them bootleggers. The KKK fanned old anti-German flames left smoldering since the First World War.

9 out of 10 Americans are ready for the end of Prohibition

By the early 1930s, even federal leaders recognized Prohibition was a failure. A 1933 referendum to ratify the 21st Amendment and repeal the 18th Amendment passed with voter approval as high as 90%. Missouri ratified the 21st Amendment on August 29, 1933.

After nationwide repeal in December 1933, wineries, breweries, and distilleries could reopen, but recovery was slow. It would take decades for the vines to grow back, for the barrels to roll again, for the Rhineland to find its voice in the marketplace. But the people remembered. Not just the wine. Not just the hardship. They remembered the dances, the neighbors who kept silent, the sheriffs who turned a blind eye, and the hands that passed bottles not out of lawlessness, but loyalty.

It would take more than thirty years before any wineries could begin significant exports, with Stone Hill Winery in Hermann being among the first to re-establish. The “Noble Experiment”, as dry supporters called it, was over.

In time, the streets ceased running red with wine, but the bitter taste of those dry years lingered long in everyone’s memory. Though the cellars sat quiet and the vines withered, something older than wine endured — a deep-rooted pride of what had been accomplished, passed down like heirloom seeds.

Even as the last stills were smashed and the dance halls grew less raucous with time, neighbors remembered. Not just the hardship, but the grit. The laughter behind barns. The bottles passed at arm’s length in defiance of distant lawmakers.

And though Missouri’s Rhineland would never again flow with the bounty it once knew, its people — sons and daughters of vintners and farmers — held fast to something stronger than law: the resilient, enduring spirit of the land they called home and their family’s ancestry in wine making and brewing.

Want to learn more?

More about Prohibition in Warren County is in the members-only newsletter from local historian Cathie Schoppenhorst. Become a member today to get more local history delivered monthly.