Sears Roebuck and Co. introduced its catalog in 1893. Three years later, the United States Post Office introduced Rural Free Delivery in 1896. Almost overnight, the Sears Catalog competed with the Bible, newspapers, and Ben Franklin’s wildly popular Old Farmer’s Almanac as the only significant reading material available in many homes.

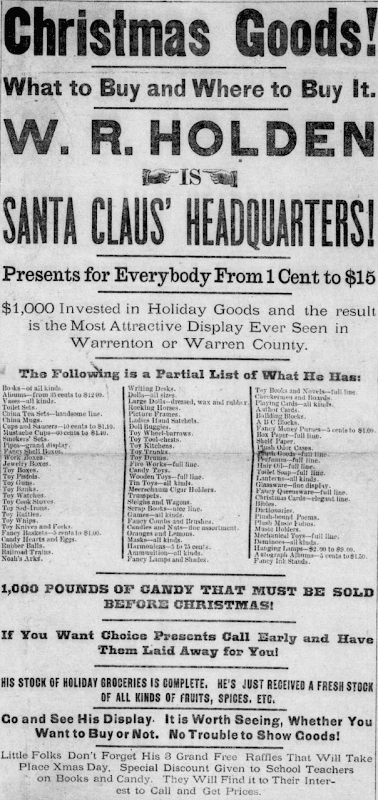

Not to be outdone, local general stores stocked what Sears couldn’t, like candy. An ad in the December 10, 1886, Warrenton Banner proudly boasts of W.R. Holden’s “Santa Claus Headquarters!”

Toys were certainly popular with kids year-round, but before 1970, nearly 70% of all toys sold in the United States were sold during the six weeks leading up to Christmas. Fudge, candy, and even oranges and lemons were common Christmas gifts for kids. Oranges were rare in the Midwest and northern climates. They were practical and fit neatly in Christmas stockings. During the Great Depression, an orange might be the only gift a child would receive at Christmas time.

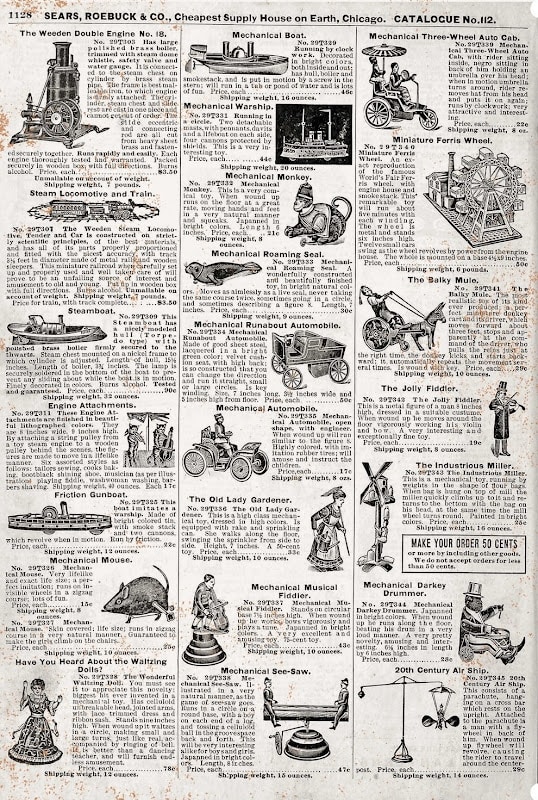

Local general stores were quick to stock the most popular items to compete with window displays, lay-away, and service. But ordering from the 700+ page Sears Catalog became trivially easy. It served as most Americans’ “wish book” by 1900 when, in a sign of Sears’ early logistical prowess, a family could order a new winter coat, along with off-season farming tools or a septic tank, and throw in a toy doll — all shipped together on a railcar.

Indeed, the poorest households and farmsteads lacked toys beyond what a child’s imagination could conjure. Playing in creeks, with sticks, or simply rolling down hills was good enough. But for those with a little extra money, rag dolls, toy anvils, carpentry sets, tin and wooden toys like locomotives and cars, and other miniaturized versions of real-life tools and jobs like toy soldiers, guns, wheelbarrows, and carts dominated children’s imaginations all year.

Fads and trends have always been a part of toy culture

Like today, toys have seemingly always come in fads and waves. Nintendo video game systems, Tickle Me Elmo, Cabbage Patch dolls, Stretch Out Sam, Lite Brites, hula hoops, and Tinker Toys to name a few more from the last sixty years. Some, like Erector Sets, only grew in popularity as war-era demand for metals limited production.

Other toys came into their own despite the war. One immensely popular fad originated with the Slinky, a 1940s discovery refined by shipbuilder Richard James. James got the idea when he accidentally knocked a tension spring off a shelf and watched it make a distinctive slide toward the ground.

Other toys followed common themes and trends, like automobiles. Among items on display in the Museum in summer 2025 is a Jewett toy automobile. The toy Jewett is modeled after its real-life model of the same name produced between 1922 and 1926.

The real Jewett’s six-cylinder 50 horsepower engine was designed to be affordable. It boasted configurations as sedans, coupes, roadsters, and closed-body options with “excellent hill-climbing ability.” Designed in Detroit by owner Harry Jewett, each car featured an amulet in the dashboard inspired by Harry’s wife, Mary. A devout spiritualist, Mary thought the amulets offered mystical protection to the motorists.

The toy cars did not feature an amulet in the dashboard, and it’s entirely possible the Jewett company produced more toy cars than real ones in its brief five-year history.

Also on display is a farm set originally purchased at Bueneman’s Hardware in Wright City back in the mid-50s. Not all items on display at the Museum have a known retailer, but many likely came from local retailers like Joseph Tomek, Sr., who maintained a thriving stock of toys at Tomek’s in Wright City. Bruning Mercantile Co. stocked various goods, including toys.

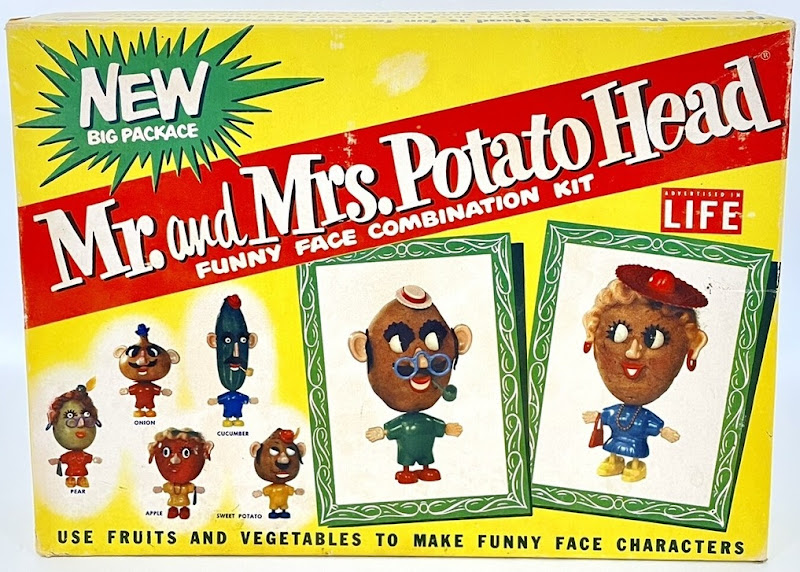

August Stamer, Sr. operated a line of shops in the region and became one of the larger and more popular “pre-supermarket” regional stores when he purchased Cooley’s Grocery Store and Meat Market in Troy, MO in 1936. There, you could likely pick up a Mr. Potato Head set and the potato (or fruit) you bought separately to dress it up with.

The lost art of play and surrender to screentime

Modern adults may find the rapid surrender of children’s toys today to iPads and screens a sad sign of the times. But this presumed stifling of imagination has been with us for generations. Millennials can remember countless hours spent playing video games on home televisions. Gen X had the arcade. Baby Boomers had television itself and semi-screened toys like Etch-a-Sketch.

In fact, you can go all the way back to April 1933 when writer Earnest Elmo Calkins wrote in The Atlantic:

Possibly the art of play is lost in childhood. I wonder if children play today as they did when I was a boy. A glance at contemporary toys convinces me that little is left for a child to do. Just the other day I saw a marvelous miniature railroad train — indeed, the complete rolling stock of a system, with engines both electric and steam, cars both passenger and freight, day coaches, Pullmans, baggage cars, freight cars, gondolas, and tanks, faithful in detail and accurately reproduced to scale — designed for boys whose parents are able to pay five hundred dollars for a toy. When a modern boy is confronted with a plaything so complete and so realistic, I wonder what he does with it. Does he get a tithe of the fun out of it that I did sixty years ago from a string of cars of oblong pasteboard box covers mounted on empty spools?

The gap between my primitive train and the real thing was the measure of my amusement. I had to fill the gap with imagination. Modern toys seem to overshoot the mark they aim at. They leave nothing for the child to do.